The Economy of Puerto Rico, Explained [Part 1]

By: Jose Sosa

In collaboration with Asociación de Estudiantes de Economía de la Facultad de Ciencias Sociales, UPRRP

This is the first in a three-part series in which we explain, in simple terms, how the economy of Puerto Rico works. Para leer la versión en español, oprima aquí.

Part 1: The Importance of Trade

Before we get started: relax. We’re not gonna talk to you about debt crisis, the fiscal control board, or the political parties. In this series, we will explain in a simple and concise way the basics of how our economy works (without it feeling like you’re sitting in a college lecture). I’ll warn you, this series of posts is a bit long, but it’s worth it to get informed about this. With that said, let’s start by discussing what an economy is truly all about (just in case you already forgot everything you memorized for your final exam way back when). The first thing we will discuss is the importance of trade.

Trade, like, I give you a dollar and you give me a beer?

Very well, grasshopper. There’s different types of trades, with the most typical in our lives being: (1) working in exchange for money (AKA generating income), and (2) spending that money in exchange for things we want and need: food, clothes, rent, Netflix (AKA consuming).

In a typical market economy like Puerto Rico, there are two key players constantly trading: individuals and companies. In essence, an economy is just the continuous flow of trades taking place between Individuals and Companies, both alternating between consuming and generating income.

Let’s start by visualizing this trading activity as a ‘circular economic flow’.

Circular economic flow? I’m getting scared…

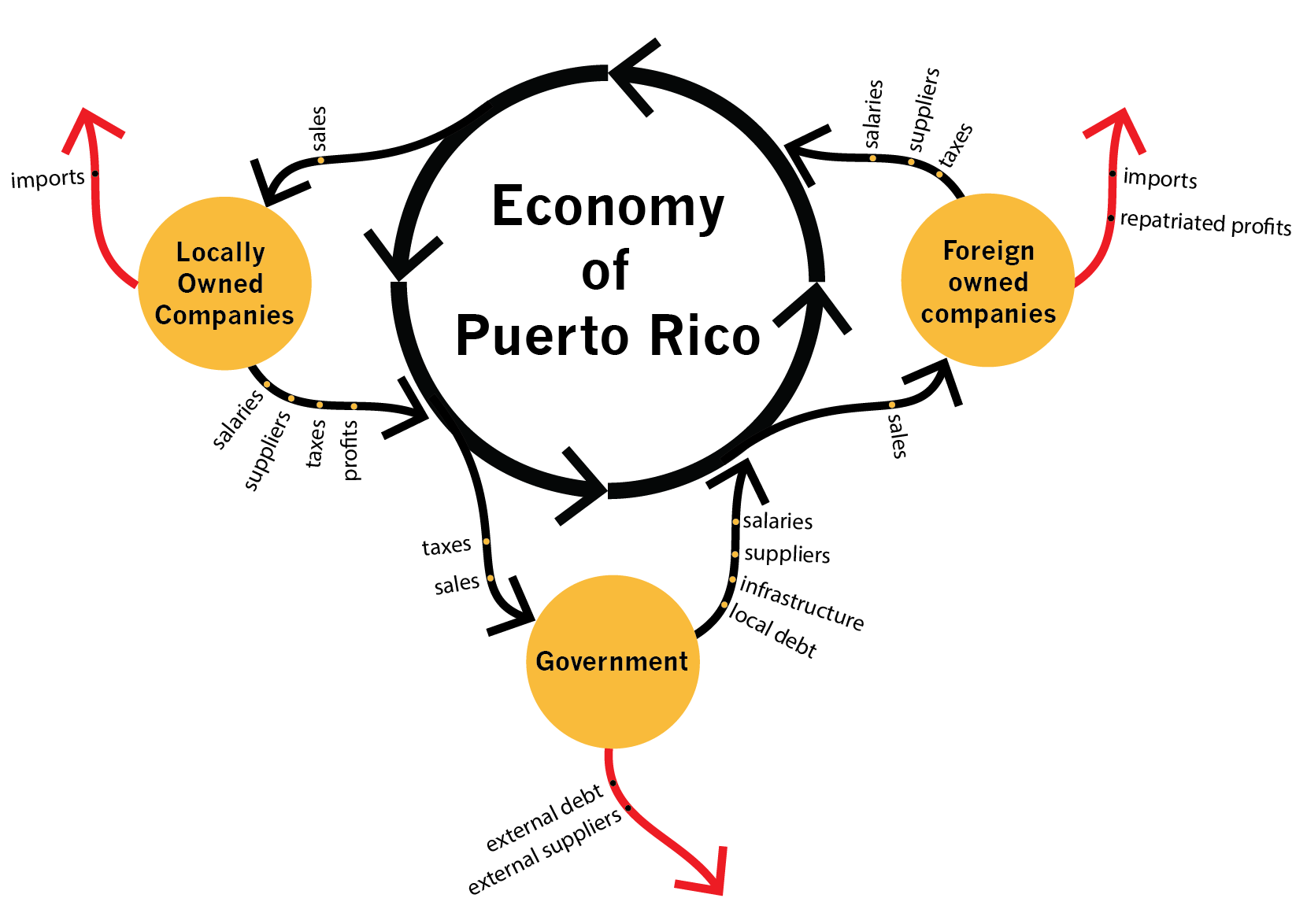

Relax, this term might sound complicated, but it’s literally just a ‘cycle’. In this case, the circle represents the Puerto Rican economy:

In this circular flow, products and services are being exchanged for money, which in turn gets exchanged for other products and services, all in a circular motion.

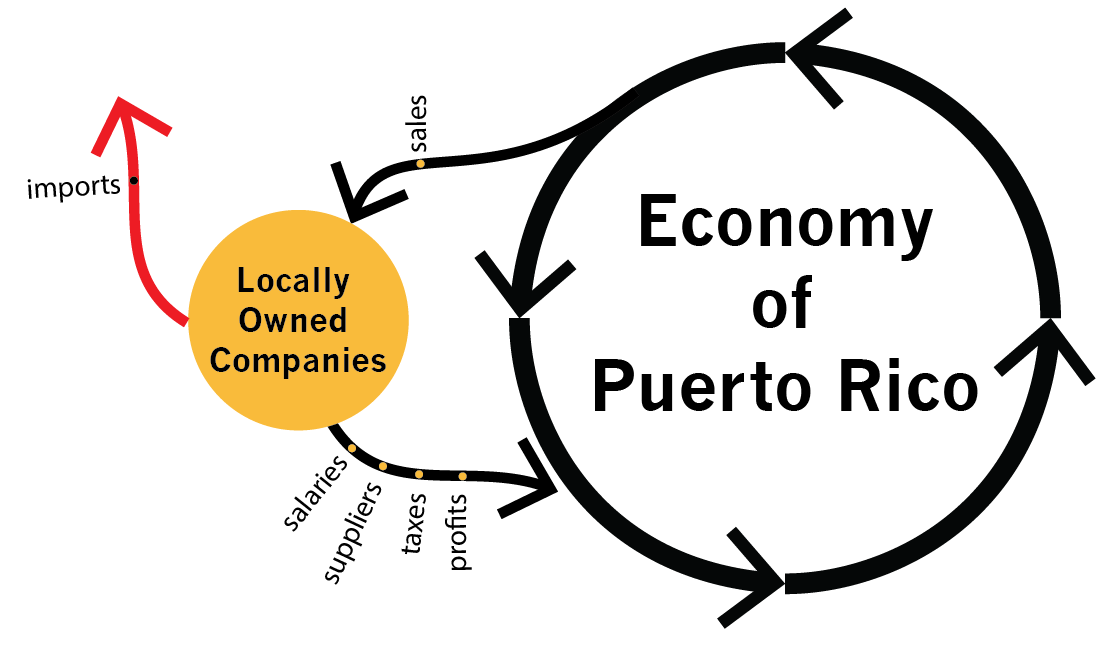

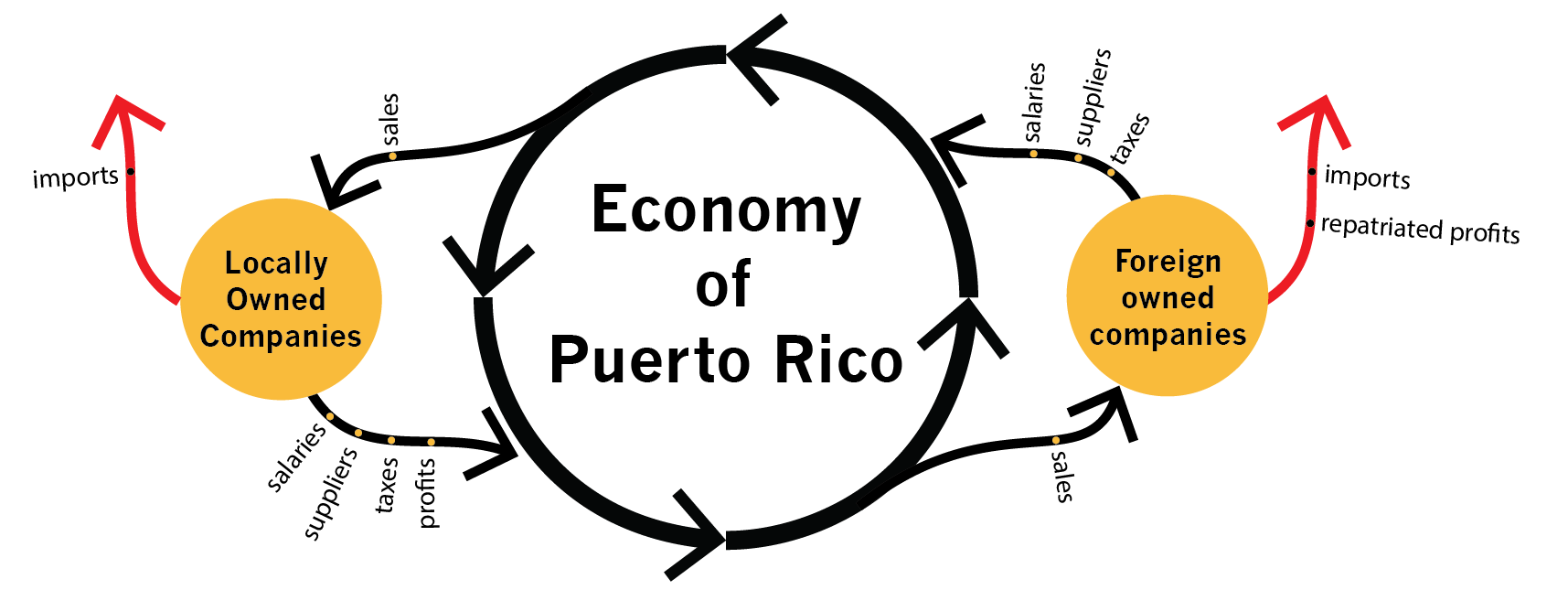

The circle has three main players, (1) local companies, (2) foreign companies, and (3) the government. Each of these players, through the different types of trades they make, contributes to the flow of money through our economy (black arrows). As we will see, some types of trades end up in money leaving the economy (red arrows), while others cause money to enter the economy (green arrows). We’ll look at what enters the economy in Part 2. Let’s take a look at the types of trades made by each of these, beginning with the locally owned companies.

Locally owned companies are just what they sound like, all commercial establishments that are owned by PR residents. This includes local restaurants, retail stores, the dentist office you haven’t been to in more than a year, and many others. Just like individuals, these companies also consume. For example, if I’m a bar in Old San Juan, I ‘consume’ every time I pay may employees, pay rent, and buy the bottles of alcohol I will later sell. The only problem is that many of these local companies have to import their supplies from foreign companies in order to operate, meaning this money leaves our economy.

Let’s now add our second majortrader in the local economy, the foreign owned companies.

These are your Walgreens and Wal-Marts, McDonald’s and Burger Kings. Mainly US owned businesses. They work exactly the same way as the locally owned companies, earning income through sales of products and services to locals, and consuming by paying employees. Similar to the locally owned companies, these foreign owned companies also import many of their needed supplies, which as we saw means this money leaves our economy. On top of that, because these companies are foreign owned, the profit distributions made to their owners also leave the economy, also called repatriated profits.

Our third key player is the government. Let’s add that in as well.

The government works similarly to a company in that it also performs the two types of trades mentioned above, earning income (AKA taxes) and consuming (mainly by paying public employees). However, some of their consumption expenses are payments to foreign suppliers as well as payments to foreign debt holders, which do not flow back into the economy.

As we can see, of the money that flows through our economy as part of the local trading activity, a lot of it leaks out. This is troublesome for two main reasons. First, because of the multiplier effect, for every $1 that leaks out of the economy, usually $2 or $3 of potential trading activity is lost. Second, if we think about the economy as an inflatable pool that leaks water, it’s easy to see how, unless we find a way to replenish that lost flow, it could soon end up empty. Similarly, these outflows of money are a constant threat of seriously shrinking, or emptying, our economy. Thankfully, we have found ways to pour water back in, but don’t get too excited because, as we will see soon, the way we replenish our economic pool is not the most ideal or sustainable. Let’s take a look at why we haven’t reached an ideal situation, starting with the multiplier effect.

The Multi-What Effect?

The multiplier effect is simply the accumulated impact that $1 can have on the economy as it gets traded multiple times. AKA: you use a dollar to buy a beer, then the owner of the bar uses that dollar to buy a pizza, then the owner of the pizza place uses that dollar to… you get the picture.

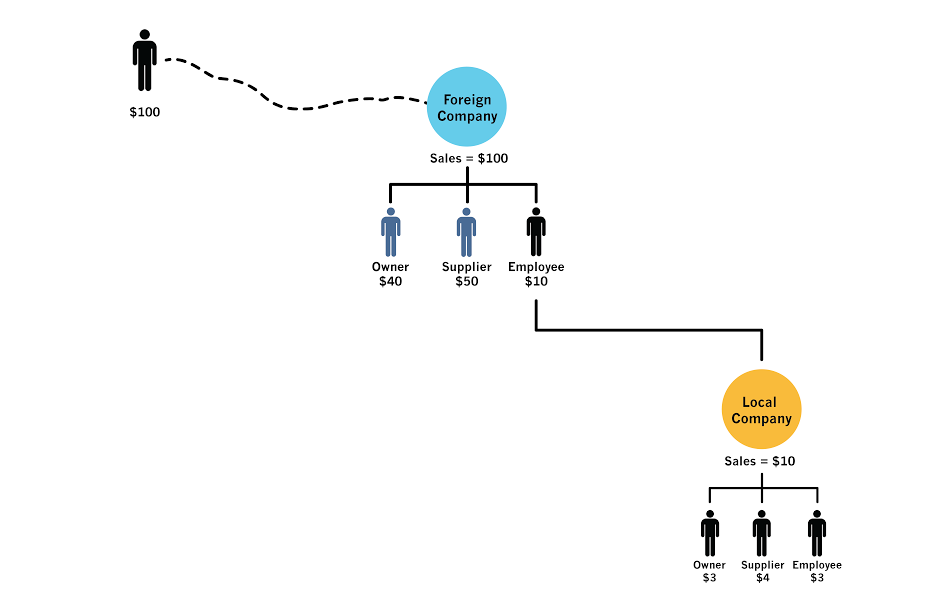

This effect can teach us about the importance not only of having more locally owned businesses, but also more local suppliers. For example, if you spend $100 in a foreign company like H&M at the Mall of San Juan, it looks a little like this:

In this case, only the $10 paid to the employee will get re-spent within the local economy. He went to a local burger shop and helped spur the local economy. BUT, the remaining $90 of the original $100 spent will leave Puerto Rico, since both the owner and the supplier are foreign.

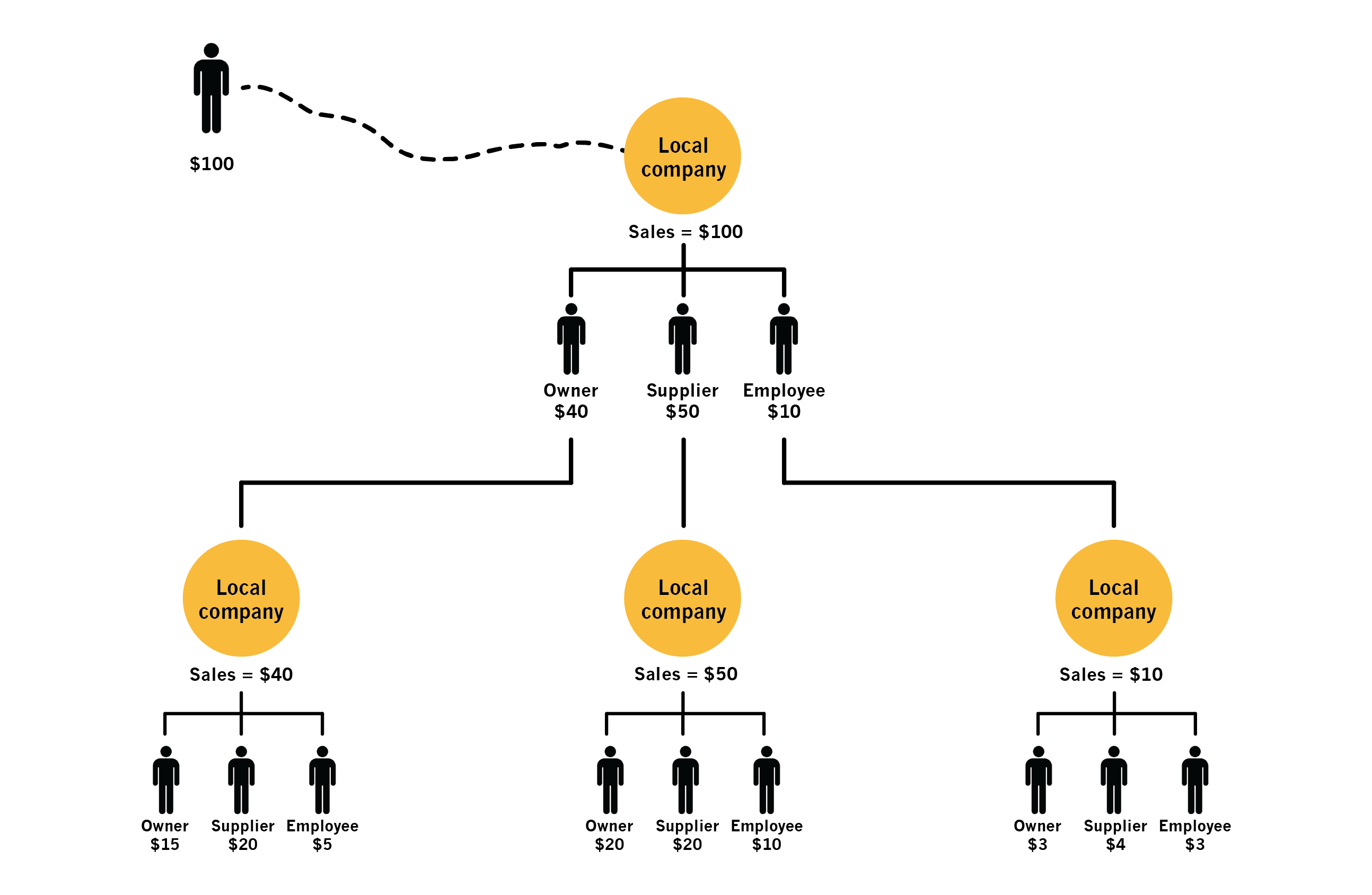

Finally, let’s see what happens when those same $100 get spent in a locally owned company with local suppliers:

In this case, the $100 get distributed to local owners, suppliers, and employees, who will then all re-spend their earned income within the local economy, creating more trades and more economic activity.

Ok… I’m done. I need a break.

No worries, we’re done.

In this first part of our series, we have seen how money leaks out of our economy by way of payments to foreign suppliers, foreign owners, and foreign debt holders. We have also seen how big an impact this money could have if it stayed, thanks to the multiplier effect. Now, you may be wondering, if so much money leaves the economy, how is it that our economic pool has not emptied out already? Check out Part 2 in order to see how Puerto Rico manages to stay afloat.

About the author: Jose is an associate at a local investment firm. He decided to write about the local economy to educate himself and help others learn about such an important topic in today’s world. He is 28 years old and lives in San Juan.

Sources

Dietz, James. 2003. Puerto Rico: Negotiating Development and Change. Boulder: Lynne Rienner.

Puerto Rico Planning Board. 2015. Statistical Appendix, Economic Report to the Governor. San Juan: Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, Office of the Governor.

_______. 2015. Balance of Payments. San Juan: Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, Office of the Governor.

Susan M. Collins, Barry P. Bosworth, and Miguel A. Soto-Class, editors. 2006. The Economy of Puerto Rico: Restoring Growth. Brookings Institution.

Machlup, Fritz. 1965. International Trade and the National Income Multiplier. Princeton University.